She was talking about the Friends of Raymond, an organization formed in 1998 with the main purpose of saving the town’s Civil War battlefield from commercial development and preserving it for its historical significance.

Now, 18 years later, FOR has the deed to about 150 acres where much of the battle was fought in 1863, and, on that land, are walking trails, interpretative plaques, a limber, a caisson and 25 cannons — 22 Union and 3 Confederate — on the locations where the originals belched forth iron and smoke on May 12, 1863.

The battle was fought just southwest of Raymond and was one of several between North and South during Gen. U .S. Grant’s invasion of Central Mississippi.

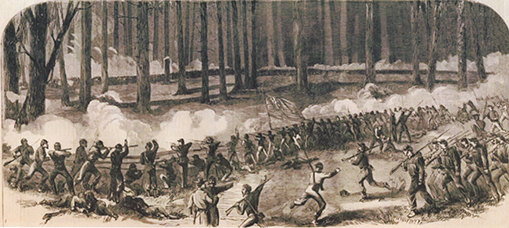

Confederate troops — they were a 3,000-man brigade under the command of Gen. John Gregg — marched up from Port Hudson, La., to Jackson and were headed to reinforce Gen. John C. Pemberton’s army when they ran into Union Gen. James B. McPherson’s 12,000-man 17th Corps.

“So, guess who won?” summed up Parker Hills, a retired general and five years president of FOR. The battle began about 10 in the morning and lasted six hours with the Confederates retreating toward Jackson.

Confederate troops also were amassed at Mt. Moriah near Edwards, and Grant, with enemies on both flanks and knowing that Confederate Gen. Joe Johnston would arrive in Jackson on the 13th, changed his plans. Hence, the fight at Raymond was a major part of his decision.

When it came to casualties, Hills said, the reports are always questionable “because you never want to admit your losses.” The South probably had about 400 killed and wounded and the North, about 375, “but it was not as one-sided as figures show,” he said. “The Rebels put up one hell of a fight, but they were lucky to get away with their breeches.”

Their escape, he explained, was a stroke of luck, though it hadn’t been planned that way. The ladies of Raymond had cooked a sumptuous meal of chicken and biscuits for the victorious Confederates. Tables on the courthouse lawn were filled with food and water and decorated with flowers, but when the Confederates began their retreat, they didn’t even pass the courthouse. Instead, they hit the road toward Jackson.

In pursuit was the 20th Ohio, whose troops couldn’t resist the aroma of Southern cooking. They stopped to partake — and Gregg’s army got away.

Wounded Confederates were taken to the second floor of the Raymond courthouse. At nearby St. Mark’s Episcopal Church the pews were removed and burned for firewood, cotton was rolled out on the floor, and the Union injured were placed there, their blood soaking through the cotton and staining the floor.

More than a century later the only pieces of evidence that there had been a battle at Raymond were 140 graves of Confederate soldiers in the town cemetery, a monument erected in 1908 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and blood stains on the floor at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. There was a marker at Fourteen Mile Creek and another on the Natchez Trace.

Parker Hills recalls speaking at a meeting of the Raymond Chamber of Commerce in 1995 when someone made the statement, “There’s one thing they can’t take away from us, and that’s the battlefield.”

Hills’ response was “I’m not sure who ‘they’ are, but they can, because not one square foot of that battlefield has been preserved.” He pointed out that the land was ripe for development — service stations, K-Marts, Walmarts, whatever.

The importance of the battlefield had caught the attention of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and a study completed in November 1997 identified it as one of the 50 most significant and endangered Civil War battlefields in the country and urged “immediate action to save this hallowed ground.”

Mayor Tullos, elected to office only a few months earlier, asked Doug Cubbison, author of the study, to address the Board of Aldermen. Both he and the mayor pointed out the potential for economic growth and historic tourism.

On Nov. 17, 1997, Mayor Tullos called Dick Kilby, president of the Merchants and Planters Bank in Raymond. There was a tone of urgency in her voice.

“I said that if we were going to commit to saving the property, we had to act immediately,” she recalled. “He agreed completely, and he and I named the original ‘cast of characters’ to begin discussing the purchase of the property.”

The desired land was 40 acres, which comprised an important portion of where the battle had been fought. Interested citizens met in the winter and spring of 1998, and, on April 13, Kilby, Tullos and David McCain discussed forming Friends of Raymond. The owner of the land said he would sell it for $4,000 an acre, and Tullos recalls that the consensus was that FOR acquire the property, not the city or county governments. On Oct. 30, 1998, with a few members signing their names and promising to repay the $156,000 loan plus interest, the first step in preserving the historic site was achieved.

In the years since, the land ownership has grown to about 150 acres, but more is needed. Creating the scene as it was in 1863 has taken untold hours of research before any items, such as cannons, could be put into place. Artisans were hired to reproduce cannon barrels to the specs of 1863. When the cannon carriages in the Vicksburg National Military Park were replaced in 2002, the old ones, made of cast iron in about 1900, were headed for the scrap heap. FOR asked for the old ones, and the answer was “yes,” if FOR would haul them off.

Members began the task, and today 22 cannons point toward Raymond, exactly where the originals were, and across the way are two on the Southern side. A Whitworth is being constructed to make the scene complete.

Funding for the cannons, at $2,500 each, came from individuals whose names appear on plaques on each gun. Hills told of one man who wouldn’t donate unless his name could be on a Southern gun, and Hills told him, “These aren’t Yankee cannons. They’re Friends of Raymond cannons.”

Money also has come from Civil War roundtables, MDOT, the Civil War Trust and other donors. When a 90th birthday bash was given for Ed Bearss, retired chief historian for the National Park service, he specified that the $10,000 plus amount be given to FOR.

“You set a goal and then you do it,” Hills said.

Memberships in FOR also have brought in the cash. Thirty-eight individuals have donated $5,000 each and are designated generals. Other memberships include several categories starting at $25. Members aren’t just from Raymond — some of the generals are from California and Pennsylvania.

Though the development and preservation of the battlefield is FOR’s primary goal, the organization also participates in the annual pilgrimage and sponsors a Raymond Cemetery Tour.

Hills and other leaders of FOR know that eventually the battlefield will be part of an overall Vicksburg Campaign series of parks. Congress has already approved the move and FOR has agreed to it, but completing the interpretation is all-important to FOR leaders. Hills said, “We are intimately associated with that battlefield. We can feel it. We want it done. We will have it done” when the time comes.

There is still plenty of work to be done, and Hills advises to be active, “Put on a pair of work gloves. We get dirty.” And if you can’t be active, send donations or memberships to Friends of Raymond, P.O. Box 1000, Raymond, MS 39154.

Ben Fatheree, retired history professor and current president of FOR, noted that “The great thing about FOR is that we have not gone to Uncle Sam for anything. Nobody had to do this. It’s all volunteer. It’s a labor of love.”